Drop by any neighborhood bar, and not much will seem to have changed in the past several years: a majority of the patrons will be drinking beer, and most will be the products of the biggest American brewers. Almost all the brands, regardless of their place of origin, will be of the international pale lager style, and about half the glasses will contain the “light” version.

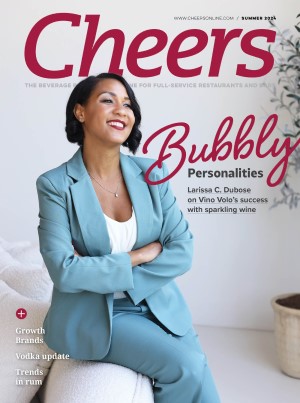

MARKETEAM INC. / SVOBODA PHOTOGRAPHY

But look a little closer at the beer list. There is probably a Heineken, Amstel or Corona on offer—imported beers, but also in the same style category as the Buds and Millers on tap. Alongside the mainstream lagers, there will likely be one or more ale, whether imported Bass Ale or Newcastle Brown, or the American micro Sierra Nevada Pale Ale. And it no longer raises eyebrows, even in traditional bars, to hear a customer ask for wheat beer styles such as Blue Moon or Pyramid Hefeweizen.

Americans are taking for granted a wider range of beer choices, not just in brewpubs and specialty multi-tap beer bars, but also in large chain outposts and independent restaurants.

To the brewing industry, these changes, though slight compared to the total volume, are evidence of a profound shift. The small, steady erosion in the market share of the American Big Three—Anheuser-Busch, Miller (SABMiller) and Coors (Molson Coors)—gave rise to anxiety in the boardroom and, a few years back, even panicked headlines asking, “Is Beer Dead?”

Over the same period, two other segments of the brewing world have done very well: American craft beer is enjoying robust annual growth and imported beers have made gains. And within domestic brews, light beer continues to grow. In fact, domestic light beer and craft brews actually off set losses by mainstream American brews in 2006. As a result, domestic beer overall is estimated to be flat after registering a 1.3 percent decline in 2005, according to Adams Beverage Group research.

As large brewers work to turn the tide and small brewers strive to consolidate their gains, both have their eye on the same opportunity: the broad American middle ground. The American drinker is trading up, analysts say, seeking more variety and sophisticated flavors.

But look back at that neighborhood bar, or the chain restaurant next door. The numbers that have shocked the brewing industry may only translate into a few more customers each evening who are open to an alternative to conventional lager. Operators must gauge how numerous and adventurous these customers really are and figure out how to satisfy them, while brewers try to channel consumer restlessness in the direction of their own products.

CHANGING IMAGE OR FLAVOR

Faced with this challenge, the large American brewers have pursued two courses of action: change the image or change the flavor. The first effort borrows from the success of imports, the second from craft beer.

Beer and beer glassware is prominently displayed at Four Points by Sheraton locations…

Anheuser-Busch president August Busch IV stated in a written message, “Consumers want choices and we are working aggressively to provide them. This includes imports, crafts and our own broad range of beers.”

In reality, the success of most imports relies on an image of sophistication. The Big Th ree American beer marketers have all acquired or partnered with imported brands within the past few years.

…where the Best Brews Program further differentiates the lounge

experience with offerings such as the Beer Sampler

“On the import side, we’ve got brands like Peroni and Pilsner Urquell and we’re also starting to tap on our parent company’s deep bench of international brands,” says SABMiller spokesman Pete Marino. “We’re bringing in three brands from Latin America—Aguila from Colombia, Cusque