Every country has a signature spirit unique to its culture and terroir. A seminar and tasting on May 8th shed some light on the grape brandies from Bulgaria and Greece. Held at Corkbuzz in New York, the “2 Cheers” session was part of a campaign financed with aid from the European Union, Greece and Bulgaria.

The Greek brandy Tsipouro is the same as Italian grappa, said Antonis Giamalidis, the technical director for the Agricultural Cooperative of Tyrnavos and Distillery. Located in the central part of Greece, near Mount Olympus, Tyrnavos is one of the largest wineries in the country, producing 6,000 tons of wine and 400 tons of spirits.

Made from the pomace (waste material) from making wine, tsipouro is known as arak in the Arabic countries, Giamalidis said. The tsipouro from Tyrnavos is made from black muscat grapes and it can be flavored with herbs and spices. In addition to its core tsipouro, Tyrnavos makes expressions flavored with anis and saffron. The company also offers an Old Spirit tsipouro that’s been aged in oak barrels for five years.

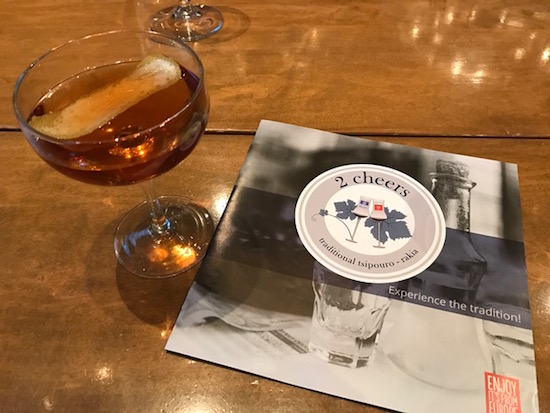

While it’s typically enjoyed on its own, tsipouro also works well in cocktails. To showcases the spirit’s potential in drinks, 2 Cheers kicked off with a cocktail called the Zeus (shown above). A take on the Manhattan, Zeus incorporated tsipouro, sweet vermouth, simple syrup and Angostura bitters.

Meanwhile, Bulgaria’s signature spirit is called rakia. But it’s not a grape brandy like Cognac, nor is rakia exactly like Italy’s grappa. That’s because it’s made from fresh wine, not the pomace, says Panayot Nikolov, coordinator for the Regional Vine and Wine Chamber of Burgas, Bulgaria.

The country is ideal for growing grapes and making wine, he said, but Bulgaria’s Burgas and Pomorie region, along the western coast of the Black Sea, provides the ideal terroir for rakia. While Bulgarians also make rakia with fruits such as plums and apricots, traditionally it’s distilled from aromatic grapes such as muscat, red misket and gewurtzraminer.

Producers evaluate the ripeness and acidity of the grapes for making the best rakia—not wine, Nikolov said. “You want more acid for distilling.” The wine is distilled immediately to capture the freshness of the fruit and deliver the character of the source, he added.

Unlike brandy, rakia is not consumed after meals, Nikolov pointed out. Rather, Bulgarians traditionally enjoy rakia at the start of the meal, with the salad course.