Kentucky bourbon remains one of the hottest alcohol categories, helping American whiskey grow 10.5% in revenue last year. Our modern brown spirits boom is far from finished. Much the opposite, consumer interest continues to spike.

Top distilleries have planned accordingly. During a media tour as part of Bourbon Classic 2023 — a multiday, Louisville-based festival that celebrates the best of Kentucky whiskey and cuisine — we visited a number of the most prominent local producers. Meeting with master distillers and executives, and touring facilities, we saw firsthand where the industry stands today, and what these companies expect for the future.

Buffalo Trace Distillery

Mecca for most bourbon fans, Buffalo Trace is in the final stages of a $1.8-billion expansion. This includes the recent completion of a second, duplicate still, seven feet wide, mirroring the existing still down to minute modifications. Eventually, this will double production.

But not yet. At most, the two stills overlap for only eight hours at a time, according to Master Distiller Harlen Wheatley. How come? The new still went up faster than the construction of additional storage facilities.

To that end, Buffalo Trace continues to erect rickhouses at a brisk rate. Along green hills overlooking the famous campus, the company for years now has built a brand-new warehouse every two months. Problem: They ran out of room up there. Solution: Buffalo Trace recently bought a farm seven miles from their cooperage, where they plan to put 17 more rickhouses. Still, they need more resting space for the increase in barrels filled, Wheatley says. If you have a farm to sell in north central Kentucky, you know who to call.

With more stills and warehouses comes other production additions, including a dozen three-story fermenters, doubling the total number. Eight more fermenters are in the offing.

In the meantime, whiskey fans flocks to this historic campus off the Kentucky River in Frankfort. Buffalo Trace anticipates more than half a million people will make the pilgrimage in 2023. Hence why the facility’s visitor center has tripled in size in the past few years.

James B. Beam Distilling Co.

The distillery behind Jim Beam continues to expand their Clermont campus with modern construction that complements centuries of whiskey history. This includes the 2021 opening of the Fred B. Noe Distillery, named after the gregarious, seventh-generation master distiller, who now shares his title with his son, Freddie Noe.

At this state-of-the-art facility, Freddie will oversee production of premium products. Booker’s, Baker’s and Little Book all have a new home, which will also house the company’s whiskey experimentations. The new distillery is not yet open for public tours. That date remains TBD.

Other tidbits: A batch of much-sought-after Booker’s Rye, with production overseen by Freddie, is currently at rest. The release schedule is anyone’s guess. As for the first Booker’s Bourbon release of 2023, the name is “Charlie’s Batch,” recognizing the man whose company builds all those iconic boxes for the cask-strength bottles.

Angel’s Envy Distillery

Like other distilleries, Angel’s Envy reacted to the bourbon boom and Covid slowdown by enlarging their visitor center during the pandemic. That $8.2-million expansion is now finished, growing this Louisville location by 3,000 square feet. This encompasses a new event space and bar, a larger retail shop and several new tasting rooms. Annual guest capacity went up by 64,000. Altogether, these new additions have the look and feel of the finest guest experiences in Napa or Sonoma.

Also new at Angel’s Envy: The master distiller. The company recently hired former Stranahan’s Head Distiller Owen Martin. He becomes the first new Angel’s Envy master distiller since 2013. This happened under the radar; securing high-level distilling talent has become significantly harder due to industry growth. Martin brings substantial experience in experimentation — including his work with Stranahan’s Snowflake — a welcome new wrinkle for Angel’s Envy and its relatively small SKU lineup. A savvy personnel move, indeed.

Michter’s Fort Nelson Distillery

Abandoned for decades, the historic Fort Nelson building leaned 23 inches into an adjacent street in Louisville’s Whiskey Row when Michter’s bought the structure. That was in 2012. Seven years later, after 400,000 pounds of supporting steel infrastructure, the beautiful site reopened with a pot still.

Nothing made at Fort Nelson has released yet, owing to aging. The company expects these first releases to hit the market sometime between 2024-26. When we visited, Andrea Wilson, Michter’s Master of Maturation, led us on a new make tasting of Forth Nelson versus the company’s distillery in Shively, KY.

Shively runs a column still (which started 24/7 production last November). New make from Shively was naturally refined, floral with lighter fruit. Out of the Fort Nelson pot still came a traditional rounder new make, herbal with darker fruit. Both were delicious.

And both will remain their own products. The plan, for now, at Fort Nelson is to put out individual, limited releases.

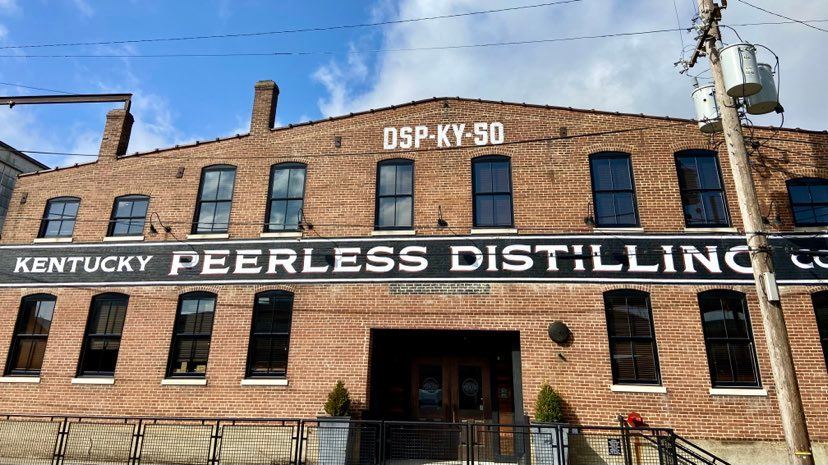

Kentucky Peerless Distilling Co.

Quiz time. We all see Peerless everywhere. Quickly, it has become nearly ubiquitous. So how much whiskey do you think this Louisville distillery produces?

The answer astounded us. Peerless only fills 10-12 barrels of whiskey per day. Earning their national profile off such a comparatively small production run is quite the accomplishment.

How did Peerless pull this off? Extremely aggressive market expansion was one answer. Another was the knack at Peerless for making correct decisions. For instance, the distillery is among a small number that runs a “sweet mash” method rather than the much more common “sour mash.” Basically, this means that the company makes each of its mashes with only fresh yeast for fermentation, rather than parts of the former mash. While the latter helps save time, a sweet mash helps prevent risk that could ruin batches, says Master Distiller Caleb Kilburn.

It’s an interesting business decision for a distillery that can trace its family ownership back five generations — and to DSP-KY-50. Not every generation of this entrepreneurial family ran a distillery. Current owner, Corky Taylor, great-grandson of Peerless founder Henry Kraver, revived the brand in 2014.

The mash bills are new, and the whiskey is coveted. Peerless Double Oak Bourbon has joined the allocated ranks more often seen on Facebook than store shelves. It’s a good problem for a fast-growing company. Due to the previously mentioned staffing shortage, Peerless does not yet distill 24/7. Plans do call for an additional rickhouse in Henry County, doubling the company’s warehouses.

As for increasing distilling? “We have dreams of growing production,” says Kilburn, with emphasis.

But Louisville and surrounding whiskey regions are now the land of bourbon dreams becoming reality. What was unthinkable during the industry’s recent nadir in the early ‘90s has become an astounding reality. Kentucky is the new California wine country, treating an exponentially rising number of tourists to elevated drinking and dining experiences. No end is in sight for our modern bourbon golden age.